Q&A with author of ‘Muse’, Ruth Millington: “Contemporary female artists today are treating their subjects with humanity“

Ruth Millington, Head of Careers at Sotheby's Institute of Art in London and author of the book ‘Muse: Uncovering the Hidden Figures Behind Art History’s Masterpieces’, tells us about how she came to write a book delving into the role of artists’ muses, why she believes muses are just as important as the artists who depict them, and how their role in the art world has changed in more recent years.

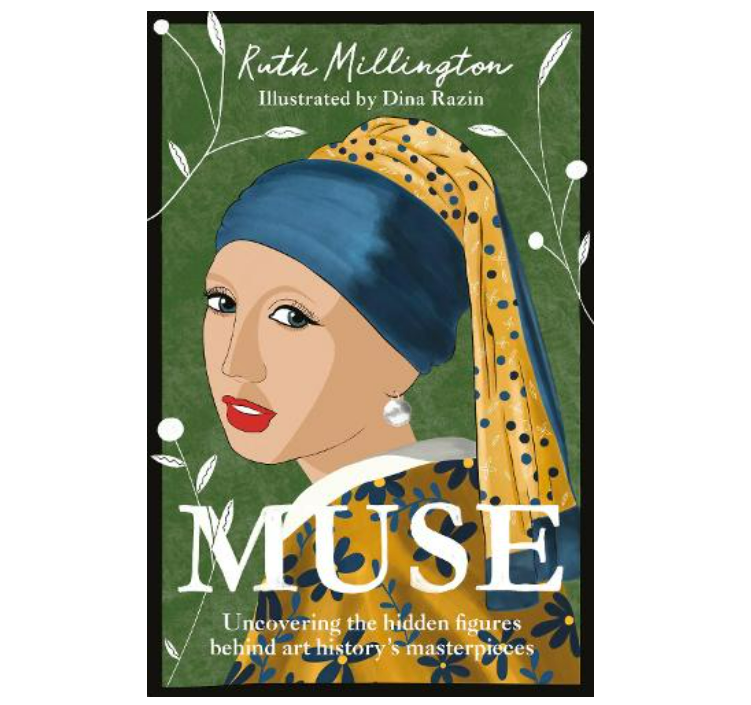

‘Muse’ by Ruth Millington

‘Muse’ by Ruth MillingtonWhat led you to write Muse: Uncovering the Hidden Figures Behind Art History’s Masterpieces?

I was writing an article for a fashion magazine and the editor asked me not to use the word ‘muse’ and use the word ‘legend’ instead. So I started digging and I came across an article by Jonathan Jones in the Guardian in which he said ‘muse’ was a really old-fashioned term, and that we should lock it away in the attic. But then he went on to describe the most stereotypical muse you can imagine, who is young and female and impressionable and submissive to an old male artist. And I thought, that is just really untrue as such a lazy trope. And I thought, is there a more celebratory way of thinking about these women but also men who've been muses?

There are way more women than male muses of course. How did you use the word ‘muse’ in your book?

Yeah, there've been so many more female muses, mainly due to women not having been able to study in the same way that men have in academic institutions. In my book, I describe a muse as the source of an artist's inspiration and point out that there is a difference between a muse and a model. So not everybody who is a life model is a muse, and not everybody who is a muse has modelled because you can inspire artists in other ways, not necessarily with your appearance. A lot of muses have been performers in some way, or musicians or dancers or actors. I explain how a lot of women artists have been muses because there is a creative exchange between two. These men have really benefited from other female creative artists. They're getting the credit, but actually many are fellow creators in the studio.

Claude Monet. Painting 1 - Coquelicots, La promenade (Poppies), 1873, Musée d'Orsay, Paris; Painting 2 - The Magpie, 1868–1869. Musée d'Orsay, Paris

So you mean that muses are just as important as the artists that depict them?

I think that's often the case. Where would so many of these great male artists be without their muses? They need a subject and obviously I'm talking about real life individuals, but broader than that, if we think about Monet, for example, the landscape was his muse. If you look at Picasso, actually you can chart all the women in his life and different art movements. It's like you can link the two together, see a real change in his direction, style, and subject matter.

Why were you so curious to explore the stories behind the muses depicted in masterpieces?

I think that goes back to when I couldn’t decide what to study at university. Originally I thought I would be an artist and then I went to art college, but I missed writing and I ended up doing liberal arts, which was brilliant. I think you can't divide the arts. You know, in a way art history is a great subject because you're bringing in philosophy and you're bringing literature and religion and politics and philosophy. And for me, a painting is like a portal into the context in which it was painted. They invite questions for me about true or fictional stories embedded in the paintings. With the pre-raphaelites, I love the fact that it's Shakespeare plays or mythology or fables that they're depicting. So I think there's so many layers of stories, the fictional story and then the real people behind it as well. I guess it's the great stories that I'm interested in.