10 of the most famous sculptures of all time

Sculptures and famous statues are a key part of our understanding of past cultures, beliefs, and events. They have the power to evoke strong emotions, inspire awe, and tell stories that resonate across generations.

Here we take a closer look at ten famous statues and sculptures from different periods — each with its own unique story to tell.

1. ‘Terracotta Army’, 259 – 210 BCE

The largest excavation pit of the Terracotta Army in Xi'an, China

The largest excavation pit of the Terracotta Army in Xi'an, ChinaOne of the most fascinating discoveries of the ancient art world, the Terracotta Army was made for China's First Emperor, Qin Shihuang (259 – 210 BCE) with the intention to protect him in his afterlife. The group of around 7,000 life-size terracotta warriors and horse figures that line the long corridors of the emperor’s sprawling tomb complex give us a glimpse of the wealth and influence the Chinese empire had.

Looking towards the east, where the conquered territories of the Qin empire lie, they seemingly face potential invaders, equipped with bronze weapons and terracotta horses.

Discovered in 1974, when farmers were digging fields near the emperor’s tomb, the site is approximately 56 sq km and around 700,000 workers are thought to have worked on the mausoleum for over 36 years.

Some art experts also believe that the Terracotta Warriors were inspired by Ancient Greek art, saying life-size sculptures were not built in China at the time and that they must have been inspired by Alexander the Great's campaigns.

Archaeologists in Xi’an, the capital of Shaanxi Province, recently found 20 newly discovered warriors, which are being restored at the Emperor Qinshihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum. The army, which remained undiscovered underground for over 2200 years, is expected to expand even further since the site Xian has not yet been fully excavated.

2. Nike of Samothrace, 190 BC

Nike of Samothrace in the Louvre © Schlaier

Nike of Samothrace in the Louvre © Schlaier‘Nike of Samothrace’, also known as Winged Victory of Samothrace, is one of the most celebrated and treasured sculptures in the Louvre museum in Paris. It was carved from marble to represent Nike, the Greek goddess of victory. Though its precise origins are unknown, it is thought to have been crafted by the people of Rhodes in the early 2nd century BC to commemorate a naval battle.

The statue was excavated on the Greek island of Samothrace in 1863 by the French diplomat and amateur archaeologist Charles Champoiseau (1830-1909). It was originally assembled out of 110 fragments, but its head and arms were never found, though a group of Austrian archaeologists later discovered part of its right hand in 1875. In 1833, the work began to gain more international attention when the Louvre decided to place it on the newly renovated Daru staircase, where it has welcomed millions of visitors to the upper galleries ever since.

The sculpture has inspired generations of artists, with Salvador Dalí paying homage to it in 1973 with his bronze and marble Surrealist work ‘Double Nike de Samothrace’. It also influenced the French sculptor Abel Lafleur (1875-1953), in his design for the FIFA World Cup trophy.

3. Donatello’s Pazzi Madonna, 1422

Donatello’s Pazzi Madonna

Donatello’s Pazzi Madonna The ‘Pazzi Madonna’, also known as ‘Virgin and Child’, was created by Donatello (1386 – 1466), one of the most important sculptors of the Italian Renaissance period. Commissioned for private devotion by a noble family in the sculptor’s native Florence, this marble relief is now held at the Bode-Museum in Berlin.

As the curators of the exhibition ‘Donatello. Inventor of the Renaissance’ point out,

Pazzi Madonna is one of the very first examples of linear perspective not only in Donatello’s work but in all Western art. The figures emerging from the marble niche seem truly three-dimensional.

The sculpture is a striking example of stiacciato, a technique that Donatello himself pioneered and which creates the illusion of depth and perspective.

Viewers of the Pazzi Madonna often remark on the intimacy and tenderness depicted between Mary and the Christ Child. Donatello showed them with their foreheads touching, facing away from the viewer, as though sharing a private moment. This was a radical departure from many of the more stylised religious images of the period.

4. Michelangelo’s Pietà, 1498-99

Michelangelo’s Pietà

Michelangelo’s PietàCommissioned by the French cardinal Jean Bilhères de Lagraulas for St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, the ‘Madonna della Pietà’, also known as ‘La Pietà’, was carved from marble by the the Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475 - 1564) and depicts a sorrowful Mary cradling the body of Christ.

‘Pietà’ was one of the only works that Michelangelo ever signed. According to Giorgio Vasari (1511-74), this was because Michelangelo overheard someone giving the credit for the sculpture to another artist of the time, Cristoforo Solari. To prevent anyone else from making the same mistake, Michelangelo carved his name on the sash that runs across Mary’s chest.

Over the years, the sculpture has been damaged several times. Perhaps the most substantial damage occurred in 1972, when the Hungarian-born Australian geologist Laszlo Toth stormed into the St. Peter’s Basilica shouting

I am Jesus Christ – risen from the dead!

and attacked it with a geologist’s hammer, removing Mary’s arm at the elbow, part of her nose, and chipping her eyelids. He was eventually subdued by some bystanders, including the well-known American sculptor Bob Cassilly.

5. Bernini’s ‘The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa’, 1647-52

Bernini’s The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa

Bernini’s The Ecstasy of Saint TeresaOne of the greatest artworks of the Baroque period, ‘The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa’ was created by the great Italian sculptor and architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598 – 1680) as a commission for the Cardinal Federico Cornaro. Held at the Santa Maria della Vittoria church in Rome, it depicts a scene from The Life of Saint Teresa of Ávila by Herself, in which the Spanish Carmelite nun recounted being visited by a divine presence.

Teresa is represented atop a cloud, while an angel prepares to pierce her through the chest with an arrow of divine love. Golden-painted beams representing rays of sunlight stream down behind them. A window concealed above the top of the sculpture casts natural light on the scene.

Bernini cleverly combines sculpture, painting, and lighting effects for maximum impact. As a result, ‘The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa’ is often used as an example of gesamtkunstwerk, or 'synthesis of arts’, a term which German writer and philosopher K.F. Trahndorff came up with to describe a work of art that makes use of all or many art forms.

6. Rodin’s ‘The Gates of Hell’, 1840-1917

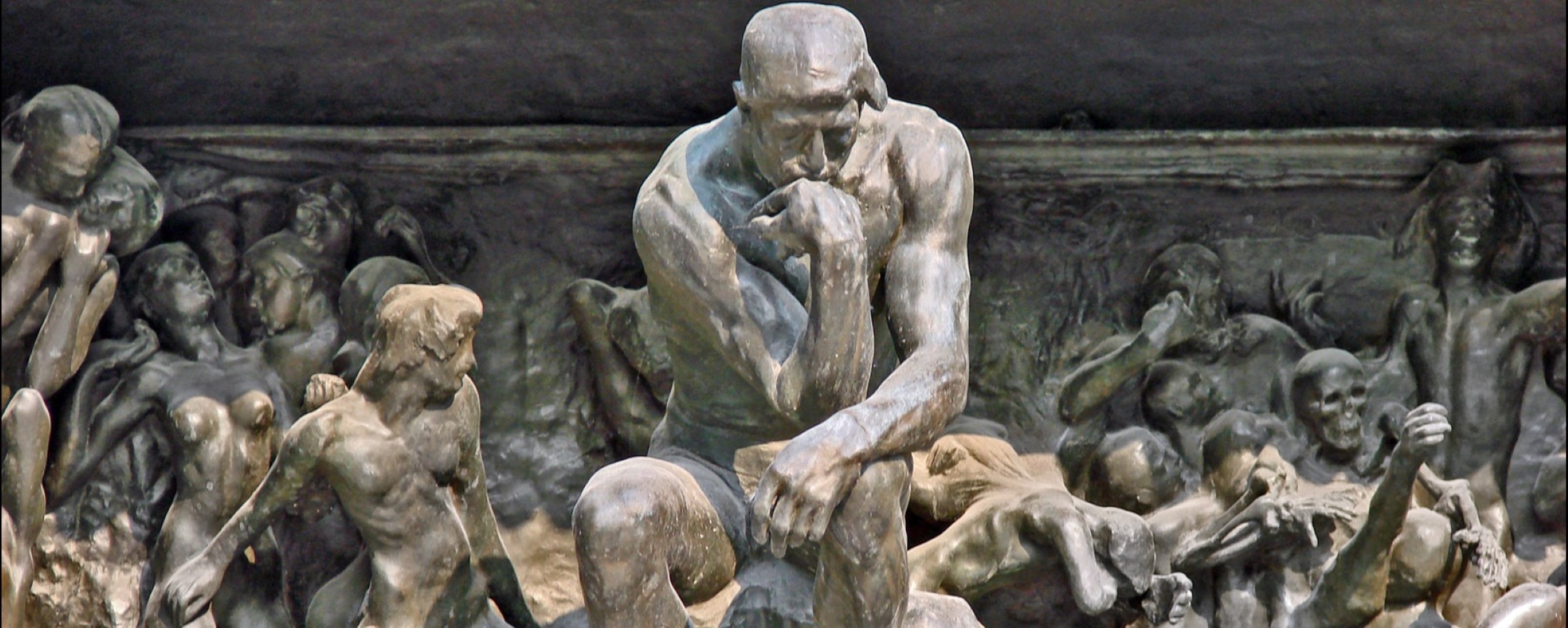

The Thinker in the Gates at the Musée Rodin

The Thinker in the Gates at the Musée Rodin A testament to his genius and passion for depicting and celebrating the human body, ‘The Gates of Hell’ is arguably the most seminal work in French artist Auguste Rodin’s career. He was commissioned to create these bronze doors for a new museum in Paris in 1880, and it took him around 37 years to complete this project.

Rodin conceived bronze sculptures like ‘The Thinker’ — which depicts a pensive, naked man deeply reflecting — for The Gates of Hell, and it was presented as an individual sculpture measuring around 70 cm in 1888. Other works he created especially for this commission include ‘The Kiss’ and ‘The Three Shades.’

Rodin took inspiration from Italian poet Dante Alighieri's (1265–1324) poem ’The Divine Comedy’, which explored the writer’s journey through Hell, Purgatory and Paradise, to create this incredible work, taking a bold and experimental approach to depict the scenes described.

This project was never completed, with Rodin working on it intermittently until his death in 1917. The Rodin Museum in Paris’s first curator, Léonce Bénédite eventually persuaded Rodin to reconstruct it and have it cast in bronze.

7. Brancusi’s ‘The Kiss’, 1907-08

Brancusi’s The Kiss

Brancusi’s The KissOne of the most famous sculptures of the beginning of the 20th-century, ‘The Kiss’ is a representation of a couple kissing. The Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi (1876 – 1957) first carved it from limestone in 1907 and later made six more casts.

As Rosalind Krauss pointed out in her book ‘Passages in Modern Sculpture’ (1977), while Marcel Duchamp’s readymades are widely anti-representational, Brancusi strove to keep his art in the field of representation. As so many other sculptors, he too was preoccupied with the work’s resemblance to human or animal forms.

The original carving is held at the Craiova Art Museum in Romania, and there is a cast at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Another cast adorns the grave of Tatiana Rachewskaia, a young Russian student who committed suicide in 1910, in the Montparnasse cemetery. Her lover, the Romanian doctor Solomon Marbais bought it from Brancusi to commemorate her. Unfortunately, due to preservation concerns, the sculpture is currently enclosed in a wooden box and cannot be viewed by the general public.

8. Giacometti’s ‘The Walking Man’, 1960

Swiss artist Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966), known for revolutionising representational sculpture with his life-size, stick-thin human figures, created his masterpiece ‘The Walking Man I’ in 1960, and it is often considered an icon of 20th-century art.

Reflecting what it is to be human, the 6-foot-tall spindly sculpture was created during a time of political upheavals and an existentialist way of thinking. Its face is loosely defined yet the work is extremely expressive, the anguished, frail figure leaning slightly forward with his extremely thin leg stretched out before him, suggesting he is walking. His arms, also very thin, are quite close to his body and if you look closely, you can see he is covered in scars.

Walking Man I was displayed at the 1962 Venice Biennale and was sold in 2010 to an anonymous buyer at Sotheby's in London for 65 million pounds.

9. Joseph Beuys’ ‘7000 Oak Trees’, 1982

German post-war artist and art theorist Joseph Beuys (1921-1986), who referred to his drawings as

the first visible form of the thought

took on this green urban renewal project in 1982 for documenta 7 — the seventh edition of the modern and contemporary art show in the West German city of Kessel.

‘7000 Oak trees’ involved planting 7000 oaks around the city, with a basalt stone accompanying each tree. Each stone was taken by the artist from a pile he had placed in front of the city's public Museum Fridericianum.

He created this project as a part of his concept of “Social Sculpture”. While the inhabitants of Kassel were not too keen at all on having this pile of the pile of rocks in the middle of their city, many locals including gardeners and activists helped plant the trees, and his work has inspired countless artists ever since.

In 2021, amid our climate emergency, British art duo Heather Ackroyd and Dan Harvey created Beuys' Acorns, which featured 100 young saplings grown from acorns collected in Kassel. The living sculpture marked 100 years since the birth of Beuys and was also created to give Londoners the opportunity to interact with art after the lockdown. Also last year, to honour the work carried out by Beuys, Tate Modern had 100 oak trees — which were the progeny of Beuys’ trees — planted outside the building.

10. Michael Heizer’s ‘City’, 1970 –2022

Complex Two, City. © Michael Heizer. Courtesy Triple Aught Foundation. Photo: Joe Rome

Complex Two, City. © Michael Heizer. Courtesy Triple Aught Foundation. Photo: Joe RomeThis colossal sculpture project in the middle of the Nevada desert measures is around the size of the National Mall in Washington, D.C, and was created by the pioneer of Land Art Michael Heizer (1944), who began working on it in 1972.

‘City’ was only finally presented in September, 2022— five decades later, and is made of concrete, rocks and dirt to form an abstract experience that is extremely limited to visitors, with only a maximum of six people allowed to see it daily through a reservation in advance. Heizer is famous for his large scale and site-specific sculptures and this is one of the largest sculptures ever created.

From Nike of Samothrace to Michael Heizer’s, these famous sculptures have stirred up emotions, inspired creativity, and even survived hammer-wielding attackers. So, the next time you find yourself in front of a great sculpture, take a moment to appreciate the stories and techniques behind it. But please, leave your geologist’s hammer at home.

Looking for more inspiring artworks? Discover how Sandro Botticelli changed art history.

Credits for the Main photo: The Thinker in the Gates at the Musée Rodin © photo by Jean-Pierre Dalbéra from Paris, France

Photo credits: © Wikipedia Commons