The Museum Barberini shines a light on forgotten Surrealist female artists

Salvador Dalí once said that fellow artist Leonor Fini was “better than most perhaps. But real talent is in the balls”. As absurd and patronising as that might sound, in practice the art world more or less concurred: for the last seven or eight decades, female Surrealists disappeared — like a magician’s assistant shut inside a vanishing cabinet.

Fini and her Surrealist sisters are now back with a bang though at the Barberini Museum in Potsdam’s superb exhibition Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity, launched in collaboration with the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice.

The first large-scale international loan exhibition to explore the Surrealists’ fascination with the occult, it features the work of Surrealist icons like Dalí, Max Ernst, and René Magritte, but also focuses on Fini (1907-1996), Leonora Carrington (1917-2011), and Dorothea Tanning (1910-2012), showing the important role these remarkable women played in the movement. Curators Daniel Zamani, from the Museum Barberini, and Gražina Subelytė, from the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, skilfully reveal how their often otherworldly subject matter concealed a real-world debate about gender.

Leonora Carrington’s witches’ kitchen

A room of the exhibition entitled ‘The White Goddess’ charts British-born Mexican artist Leonora Carrington’s lifelong fascination with mythology and the occult. Carrington may even have practised magic herself. Her friend and fellow painter Remedios Varo once wrote in a letter to Gerald Gardner, considered the father of modern witchcraft: “I, Mrs. Carrington, and some other people have devoted ourselves to seeking out facts and data still preserved in isolated areas where witchcraft is still practised.”

Carrington was particularly influenced by Robert Graves’ seminal essay ‘The White Goddess: A Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth’ (1948). Graves’ work was also a formative influence on Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath. In the essay, Graves argues that all European mythologies can be traced back to ‘The White Goddess’, a powerful deity who governs birth, life, and death. It greatly shaped Carrington’s thinking about the role of women in society, having written in a 1976 exhibition text, she wrote: “Most of us, I hope now, are aware that women should not have to demand Rights. The Rights were there from the beginning; they must be Taken Back Again, including the Mysteries which were ours and which were violated, stolen, or destroyed.”

Many of Carrington’s later canvasses appear to look back towards the mythical, matriarchal world that Graves described in ‘The White Goddess’. For example, her 1975 painting, ‘Grandmother Moorhead’s Aromatic Kitchen’ references myths that her Irish maternal grandmother told her as a young girl. In the painting, the kitchen – a traditional site of female domestic labour – is turned into a place of divine enchantment. Carrington links the simple act of preparing vegetables to witchcraft and alchemy.

Leonor Fini’s strixes and sphinxes

Another room, entitled ‘Goddesses and Witches: Women as Magical Beings’ shows how female Surrealists like Leonor Fini appropriated mythical imagery to assert their own identities. A prime example of this is her 1947 painting ‘Stryges Amaouri’, in which she depicts herself as a strix, a malevolent winged demon found in Greek myths. She is leaning over a reclining nude man entwined in ivy, in a stance that can be interpreted as protective or predatory. Here, as in many of her paintings, Fini inverts gender stereotypes.Fini often appears in her paintings in the guise of various mythical creatures – most often the sphinx. With the head of a woman and the body of a lion, the sphinx is neither an animal, nor fully human. It resists categorisation – like Fini herself, who believed that she had multiple personalities and loved to shock her contemporaries by showing up to parties wearing a cat or lioness mask. She is quoted as saying, “I have always loved and lived my own theatre.” By playing the part of the sphinx, Fini challenged conventional gender expectations.

Dorothea Tanning’s magic thread

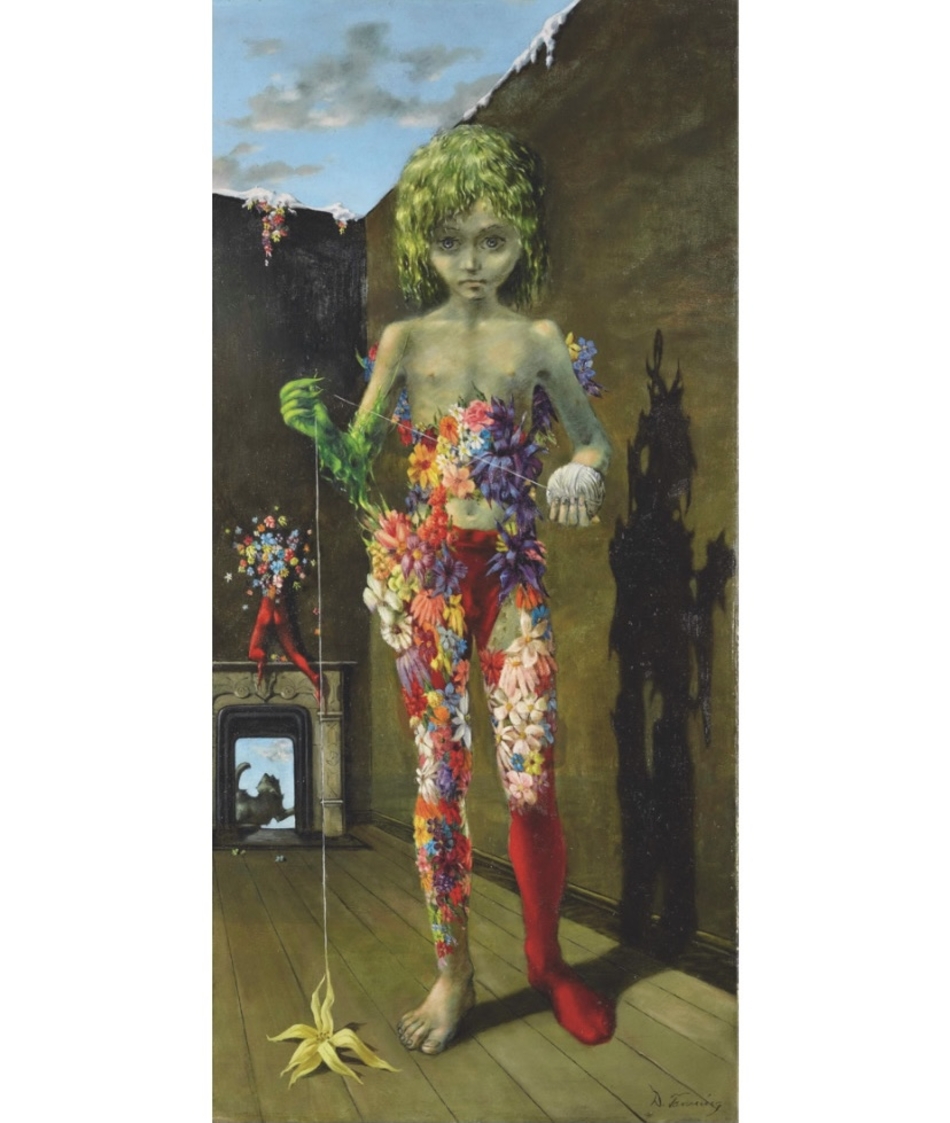

The exhibition skilfully shows how Fini, Carrington and other artists subverted and parodied male surrealists’ ideas about gender. One standout work in the exhibition is Dorothea Tanning’s 1941 painting ‘The Magic Flower Game’. It depicts a young girl who resembles a forest elf or sprite. She is half-clothed in an outfit made almost entirely of brightly coloured flowers, and she holds a ball of thread which appears to transform into a sunflower.

The ball of thread is reminiscent of Greek myths, like Perseus and the Minotaur, and the archetype of The Three Fates. Though seemingly playful, it evokes the idea that the elf girl is powerful and in charge of her own destiny. Tanning’s painting is also a visual riposte to the archetype of the femme-enfant or ‘woman-child’ that André Breton first envisioned in his Surrealist novel Nadja (1928). In Breton’s mind, the femme-enfant represented complete innocence, irrationality, and sweetness. By contrast, Tanning’s elf girl is confident and knowing.

Leonora Carrington wrote in her short story The Seventh Horse that “art is a magic which makes the hours melt away and even days dissolve into seconds.” As in Carrington’s story, this exhibition shows how, for female Surrealists, creativity and magic were inextricably linked.

Credits for the Main photo: Exhibition view, 'Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity' © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Photo: David von Becker