Zineb Sedira at the Venice Biennale 2022: What you should know before visiting the French pavilion

Zineb Sedira, born in 1963, is the fourth woman and the first artist of Algerian descent to represent France at the International Art Exhibition of the 59th Venice Biennale. The French Pavilion of 2022 was curated by Yasmina Reggad, Sam Bardaouil, Till Fellrath in collaboration with Sedira. It is based on the representation of Algerian culture in cinema and Sedira has received a Special Jury mention for her efforts.

The French Pavilion will be open to visitors until October 27, 2022 and reflects on the turning point of avant-garde production between Algeria, France and Italy. A combination of activist film, photography, sound, sculpture and collage gives the entire pavilion a very cinematic feel. Here are some interesting facts you might want to know before visiting.

The Artist

Sedira’s art is based on her own experience and childhood memories of racism and discrimination. These experiences have by default influenced her artistic interests and that is why Sedira evokes the experience of being an immigrant’s child in partly autobiographical and partly fictional narratives.

Sedira’s fondest childhood memories involved spending time with her father at the cinemas, where they saw everything from Hollywood blockbusters to Egyptian dramas. After years of exposure to a variety of cultures, Sedira cultivated an interest in art, independent films, and militant cinema, which are thematically close to the so-called “Third-World'' values and aesthetics.

The French Pavilion

The French pavilion consists of reconstructions of film sets and art installations depicting the process of creation of the pavilion on one hand, and of Sedira’s own experience and process of work on the other.

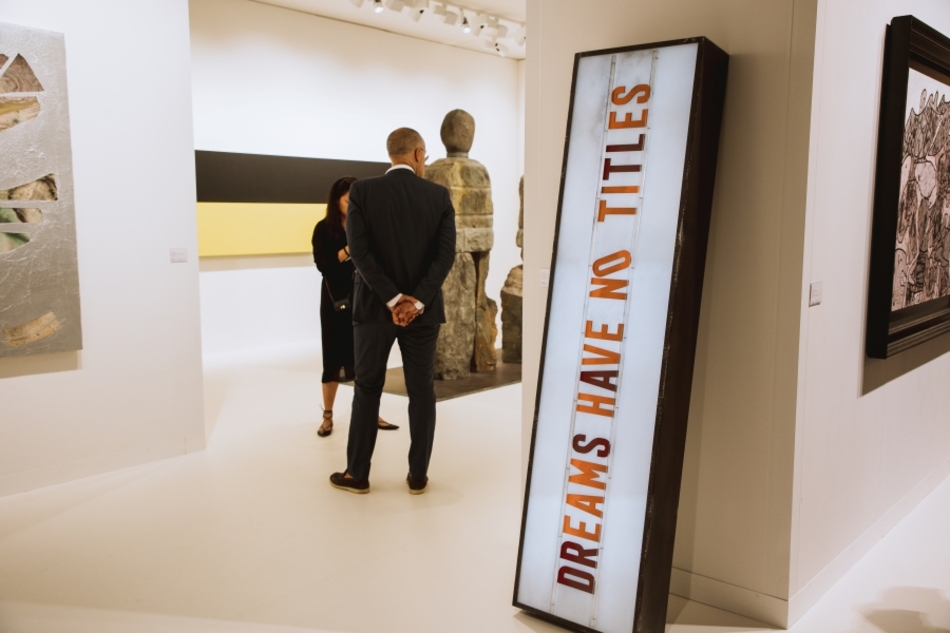

Entering the French pavilion feels like stepping into a film set. At times you are surrounded by the reconstructions of sets for real films. The three-point lighting setup makes it seem like the camera is ready and there are actors ready to perform. Several performers are actually sitting or dancing among the crowd. This gives the viewer a unique sensation of creating something as well as being a spectator.

There is also a feeling of suspension when you are here. Since the viewer hasn’t been invited to watch, the only thing left to do so is to become a kind of camera: to observe how actors interact with and within the set decor.

The film

The main focus of the pavilion is the 25-minute film ‘Dreams Have No Titles’. Rather than being an entertainment-based explanatory film, it is a research-oriented narration. It is a kaleidoscope of the fragments of films made in Algeria in collaboration with other countries, copied scenes from these films and also behind-the-scenes in which Sedira walks you through the process of constructing actual sets. Since this is an autobiographical piece, the actors are primarily Sedira’s family members, fellow curators and artists.

Sedira describes it as a “film about films”. It presents her recollections of her childhood stories and archive resources revolving around themes like the critique of the colonial legacies, collective and individual memory, national identity and also, according to the film’s title, our ability to dream.

In Sedira’s works and installations including ‘Dreams Have No Titles'’, you’ll come across Algerian films like “The Battle of Algiers'' (1966, Gillo Pontecorvo) or “Le Bal” (1983, Ettore Scola). These movies were made during or after the 1960s and are full of anti-colonialist rhetoric. It is also interesting to note how Sedira challenges a common Third World Cinema feature by using her voice to narrate the stories instead of opting for a male voice-over.

It is also worth mentioning that during the research for the project, a lost Algerian film called ‘Les Mains Libres’ (1964), by Italian director Ennio Lorenzini, was found in a small archive in Rome. This film is significantly known as the first film produced in newly independent Algeria as a product of international co-production.

The collaboration

While preparing for her exhibitions, Sedira scoured research archives in Algeria, Italy and France. These were the countries that were most actively producing Algerian films during the 1960s. The exhibition itself is a great example of the collaboration between these countries, both in the past and in the present. A visit to the French Pavilion immerses viewers beyond the Third World narrative through the artist’s own experience, while also providing an opportunity to celebrate 60 years of Algerian sovereignty.