A review of La Scala’s new production of Offenbach’s Les Contes d'Hoffmann — a dystopian opera capturing the disenchanting side of humanity

Mannequins, coffins, shadow puppets, and flaming type-writers create a dark dystopian cabaret - the setting for Davide Livermore’s new production of Offenbach’s opera, ‘Les Contes d'Hoffmann’ (The Tales of Hoffman) at Teatro alla Scala, Milan.

ETA. Hoffmann’s haunted history

‘The Tales of Hoffman’ is a fantastical conjecture on the life of the German poet, ETA Hoffmann. The poet’s own literary works focused on the darkest corners of human nature and these sombering stories have gone on to be the inspiration for many other great creatives.

French opera librettist Jules Barbier took three of Hoffman’s works and wove them together to create a biographical opera depicting the poet’s struggles with romance. It is said that Barbier and Offenbach’s intent was to depict Hoffman’s relational development, beginning with innocent infatuation, which evolves into adolescent affection, and finally winds up in lustful disillusionment.

ph Brescia e Amisano © Teatro alla Scala

Both in the opera and in his personal life, Hoffman was plagued by misfortune from a young age with his father leaving his mother at age two, his favourite aunt who raised him dying at age three, and as an adult enduring the Franco-Prussian War.

Unfortunate events also haunted the production of the opera, Jacques Offenbach having died with the unfinished score for Tales of Hoffman in hand. Just days before passing away, Offenbach pleaded to see the premiere of the work, albeit unfinished. The task of completing the work was left to his colleagues, notably Ernest Guiraud. Even when the opera was finally ready for performance, the horrors kept coming. When the opera finally made its Viennese debut, not a single note was sung. While the house lights were being lit, a devastating fire broke out which led to mass fatalities of the audience.

Alfonso Antoniozzi - ph Brescia e Amisano © Teatro alla Scala

Minimal mastery and shadow puppetry

Davide Livermore certainly captured the darkness lurking in Hoffman’s life. Livermore’s decision to set the Hoffman story in an underground cabaret was effective in communicating Offenbach's iconic pairing of tuneful musicality juxtaposed with the disenchanting side of humanity.

Offenbach was known for satirical mastery and wit, serving twisted morality in elegant tunefulness. Even in Tales of Hoffman, which was initially intended to be a ‘grande opera’, Offenbach used fantasy characters singing memorable tunes about greed, lust and deceit to serve a sugar coated truth about his aristocratic audiences.

Marina Viotti ph Brescia e Amisano © Teatro alla Scala

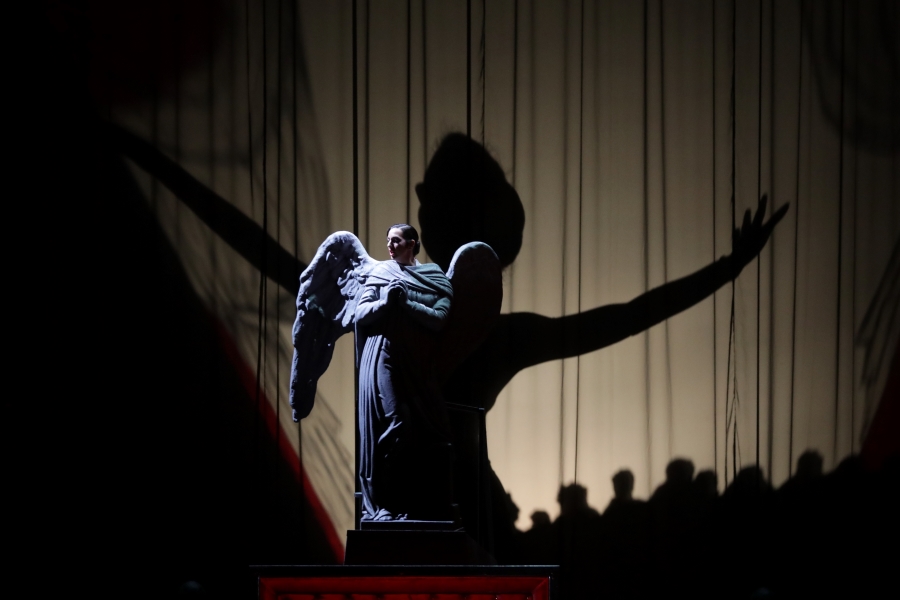

Beginning with the idea of minimalism and morality, the opera opens with a towering angel statue, which appears to be Hoffman’s ‘Muse’, played by Marina Viotti, singing the opening prologue. The Muse climbs down, leaving a headless statue, to join Hoffman’s three love-interests on a very barren stage. Throughout the production the set is largely minimal, relying predominantly on drapery, props and lighting, reflecting Giò Forma and Antonio Casto’s superb team work.

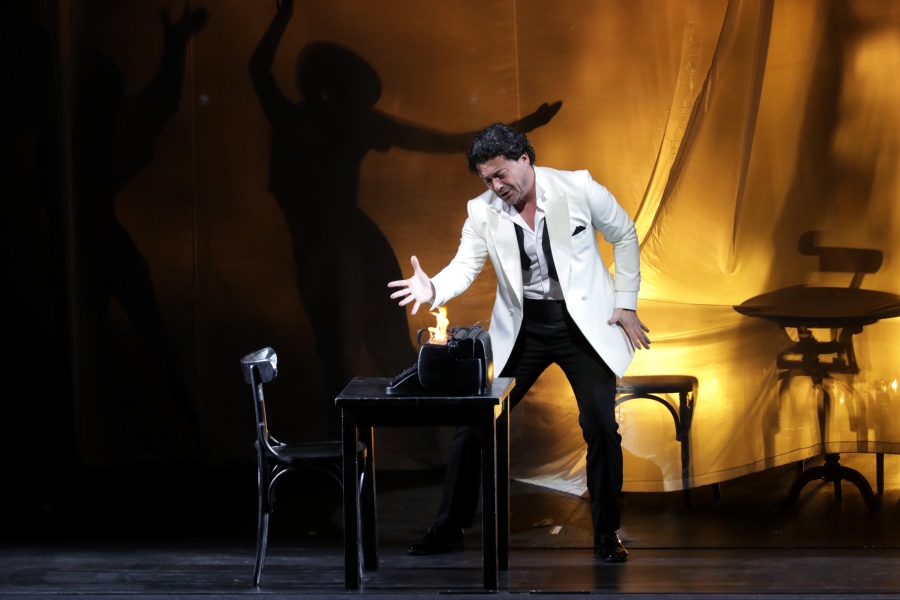

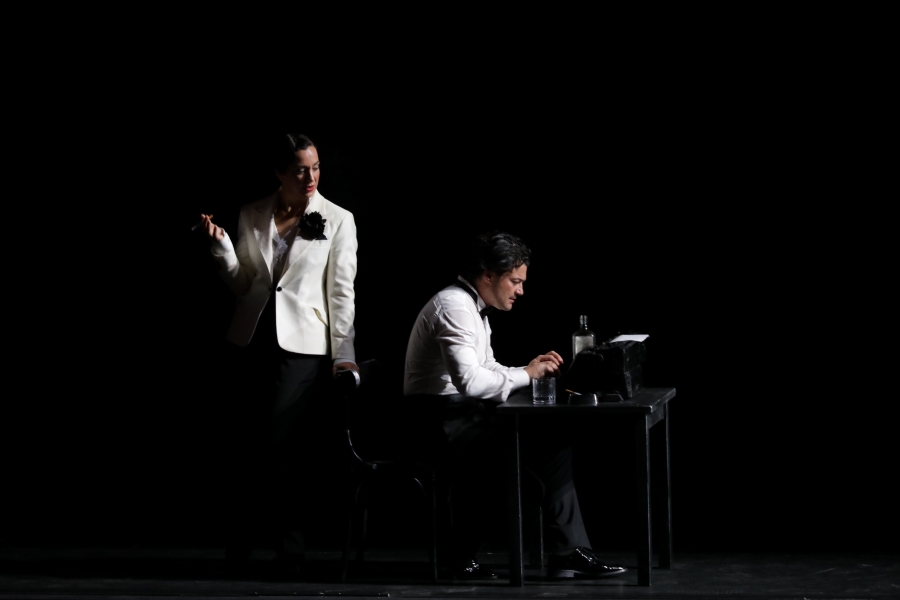

Instead of resorting to digital technology, the pair utilise the age-old art of shadow puppetry to create beautifully haunting backdrops - a pleasant surprise in the current climate of digital set design. A coffin is the centrepiece of the opening set, where we meet a deceased Hoffman. Leaving the audience to play spot the difference, another Hoffman appears from nowhere in a dapper white suit jacket roaming around the stage swigging vodka before taking his place at a typewriter. Hoffman and the typewriter glide across the revolving stage panel to signal that we are entering into the story realm of unrequited love manifested in the three women — one who turns out to be a doll, another a terminally ill singer and lastly a sex worker.

Buratto, Di Sauro, Guida - ph Brescia e Amisano© Teatro alla Scala

Psychological thrillers: The Doll Song

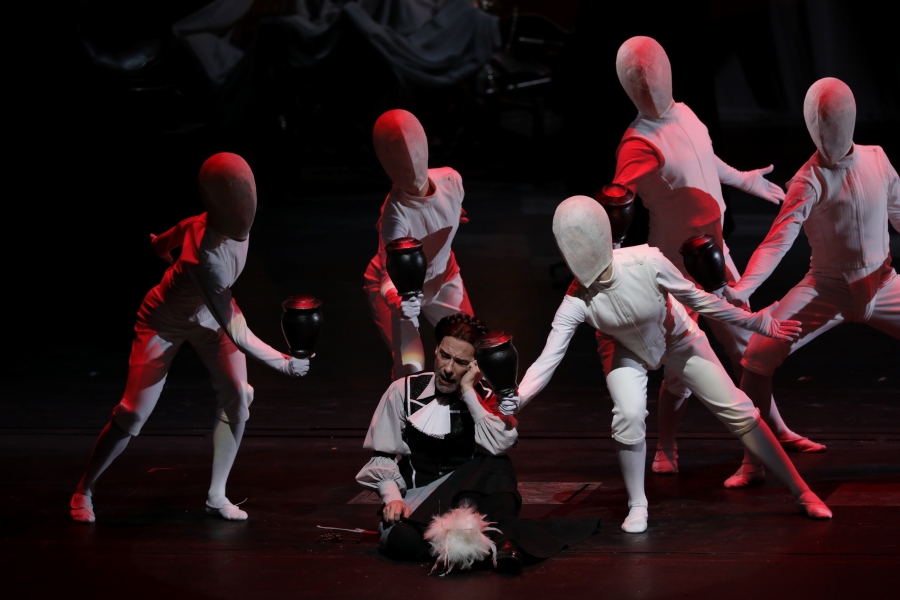

One of the most renowned pieces from Tales of Hoffmann is the Doll Song. Instead of making the mechanical doll the height of comic relief, as she is in most performances, Livermore chose to stay closer to the psychological thrillers of Hoffmann’s original stories.

Olympia’s head is painted like a ghostly mannequin, paired with a black bodysuit. The ensemble of unidentifiable fencers in black fencing uniforms, run onto the stage holding pieces of a cheap plastic mannequin to become the puppeteers of Olympia’s body. Half way through, the puppeteers run away with the body and join a chorus of 1920s aristocrats playing with mannequin heads in time with the ‘oom-pah-pah’ rhythms.

ph Brescia e Amisano © Teatro alla Scala

Abandoned in the middle of her aria, Olympia is alone on left of centre looking extremely awkward, visibly uncomfortable being exposed in her bodysuit. Although the chorus was directed to upstage the singer, thrusting the decapitated mannequin heads into the air in time with the music, Frederica Guida’s steely voice and commitment to the distraught version of Olympia remained centre stage. Guida’s instrument carries more weight than most sopranos cast as Olympia, but she was still able to effortlessly move her sound from the ledger lines back down to the bottom of the stave. This power, range and agility suggests Guida has the potential to be cast as Donizetti’s notoriously difficult Queens. She is one to watch and the audience knew it.

ph Brescia e Amisano © Teatro alla Scala

An honourable Hoffmann

Hoffman’s role is a marathon for the greatest of tenors. The ‘operetta’ period is deceptive when it comes to the demands on the tenor voice, which are closer to dramatic in delivery. On stage throughout the full length of the production, Vittorio Grigolo proved his place in the history books as one of Italy’s finest performers. Many singers don’t manage to begin in commercial records and transition into an opera legend. A charismatic stage animal with the chops of a Lion, Grigolo embodies what it means to be an operatic star. Giving full credit where it is due, while he has it all, it is clear that Grigolo works extremely hard. A singer for the people, Grigolo has analysed what matters to an audience, and instead of being distracted by internal dialogue like many great artists, he is for the people rather than in his head. Grigolo’s Hoffman was endearingly desperate, there was no doubt that he was a poet who was felt cheated by romance.

ph Brescia e Amisano © Teatro alla Scala

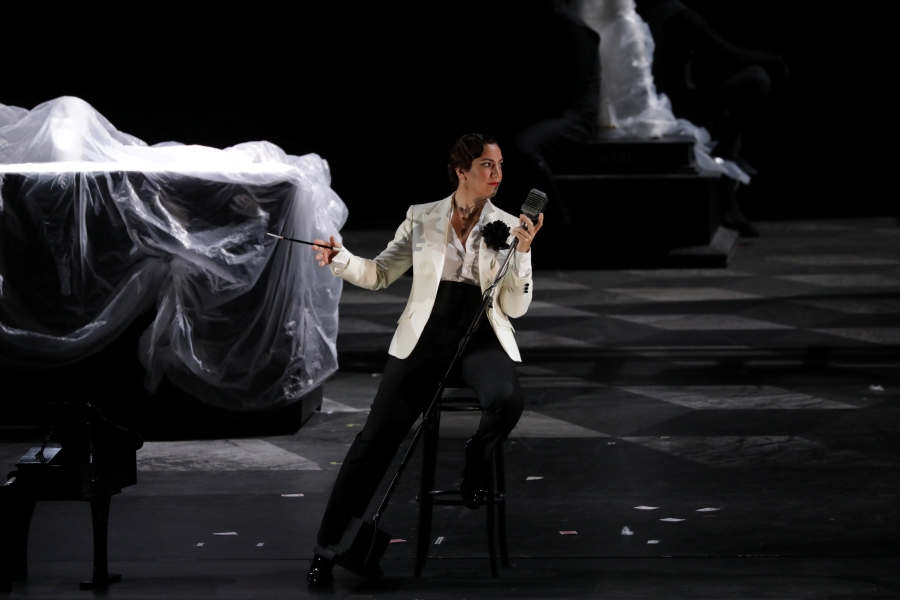

A mesmerising muse

The seasoned Milanese audience gave rapturous applause after Marina Viotti’s ‘Violin aria’, an easily underestimated piece, which the Swiss Mezzo made light work of. Another magical moment was when Viotti took hold of a 30s styled mic on a stand and sang into it like a midnight jazz crooner. Boldly singing with a sound closer to her spoken voice, and without any operatic amplification, silenced the audience. Unexpected moments often make for the most memorable - the courage to get vocally naked, and sing into a live mic and stop the opera for a moment felt undeniably vulnerable.

A versatile cast

Act two is one of the most sentimental pieces of Offenbach’s writing. This act documents the final moments of the young singer, Antonia’s life, who is arguably Hoffmann’s most sincere romantic encounter. This act was said to have been written by Offenbach at the time he became aware of his own impending fate. An experienced lyric soprano, Eleonora Buratto captured Antonia’s temperament well.

The most powerful moments of Buratto’s performance were her spinning pianissimo that sent overtones ringing throughout the theatre. Unlike other productions which leave ‘the Voice’ off stage or as a hazy figure, Livermore chose to make it unequivocal that Antonia’s mother was returning from the grave as a 20s flapper wrapped up in sheer black fabric. Francesca Di Sauro made for a compelling actress, embodying Une Voix as an elderly lady, then showing her versatility, transformed into Hoffman’s last love interest, a feisty young courtesan, for the third act.

ph Brescia e Amisano © Teatro alla Scala

Playing all manifestations of the temptor, Luca Pisaroni was a safe pair of hands for the bass-baritone roles, as was the case with Francois Piolino’s light relief as Andrés, Cochenille, Franz and Pitchinacchio. A strong cast all round — with Greta Doveri as Stella, Yann Beuron as Spalanzani, Nestor Galvan as Nathanaël, Hugo Laporte as Hermann and Schlémil, Alterno Rota as Un Voix, and Alfonso Antoniozzi as Luther and Crespel — no role went unnoticed. With Frédéric Chaslin’s baton at the helm, there was fine leadership and propulsion of the everchanging score and demonstrable understanding of the French impresario style.

The work of Livermore, Forma and Casto made for a retelling of Hoffmann that aligned with the French era in which it was written, but which also translated for today’s audiences with stylistic choice and timeless symbolism. The minimal sets and return to traditional means of story-telling transported the theatre to a more Bohemian time, and as Offenbach intended, provided a sense of light-hearted entertainment but also introspection about the pitfalls of humanity.

Davide Livermore’s new production of Offenbach’s opera, ‘Les Contes d'Hoffmann’ runs until March 31.

For more ideas for inspiring performances and other events to attend, check out our pick of the 16 must-see cultural events in 2023.

Credits for the Main photo: ph Brescia e Amisano © Teatro alla Scala