5 Famous muses: How they inspired the greatest masterpieces

Throughout art history, the muse has been placed on a pedestal as an intangible, almost mythical creature. Simultaneously though, they've also faded into a silent obscurity, removed from the creative process.

Goddess of the arts: Artists’ muses

In Graeco-Roman oral tradition, poets like Homer and Virgil would invoke the three muses as a source of artistic skill, knowledge and inspiration. While this mystical perception of the (largely) female ‘muse’ has remained, what was once an emblem of creative authority in constant dialogue with the artist has ultimately become a neglected and passive visage of beauty.

Often fascinating characters in their own right, seeking to infiltrate male-dominated artistic spaces, art history’s most fascinating and prolific muses can tell us a lot about contemporary ideals and offer insight into the headspace of the artists and the cultural and aesthetic shifts behind their respective milieus and movements.

Here we look at some of the most famous artists’ muses in history and the iconic artworks they inspired.

1. Elizabeth Siddal

Ophelia, John Everett Millais, c. 1851–1852 © Tate Britain, London

Ophelia, John Everett Millais, c. 1851–1852 © Tate Britain, LondonMost famous for her appearance in John Everett Millais’ Ophelia (1851-2), Elizabeth Siddal was a favourite model of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, posing for the likes of Walter Deverell, William Holman Hunt and her eventual husband, Dante Gabriel Rosetti. With gaunt features, a willowy build and vibrant copper hair, Siddal defied Victorian standards of beauty and helped to shift perceptions of the feminine ideal from delicate, humble and submissive to bold, assertive and self-assured.

More interestingly, her unconventional look spoke to wider anxieties about decorum and virtue amid the social upheaval of Victorian industrialisation. Her look was not merely decorative but an integral symbol of the Pre-Raphaelite rebellion against didactic Victorian art.

Yet Siddal was not just a blank canvas for which the Pre-Raphaelites could paint new ideas of art and culture. A student of the Sheffield School of Art, Siddal was proclaimed a "genius" by art critic John Ruskin, who subsidised her career and paid £150 a year in exchange for all the drawings and paintings she produced. Having not been born into an artistic family and lacking the money to pay for training, assuming the role of the "muse" may well have been the only route for a woman like Elizabeth Siddal into a male-dominated artistic space.

2. Emilie Louise Flöge

Emilie Flöge, Gustav Klimt, c. 1902 © Wien Museum

Emilie Flöge, Gustav Klimt, c. 1902 © Wien MuseumEmilie Louise Flöge is best known as Gustav Klimt’s life companion and business partner, however her practice as an avant-garde Viennese fashion designer pioneered a revolution in womenswear, helping to free the female silhouette from the shackles of corsetry and modesty at the fin de siècle.

Klimt first painted Emilie as a 28-year-old, covered in a floor-length dress of her own design. Characterised by detailed, ornamental patterns, opulent colour palettes and eccentric, bohemian silhouettes, this piece marked a turning point in Klimt’s style. This artistic symbiosis enriched both of their practices, as many women of the Viennese upper-class visited Emilie’s studios to order similar designs and portraits after seeing Klimt’s paintings.

3. Lydia Delectorskaya

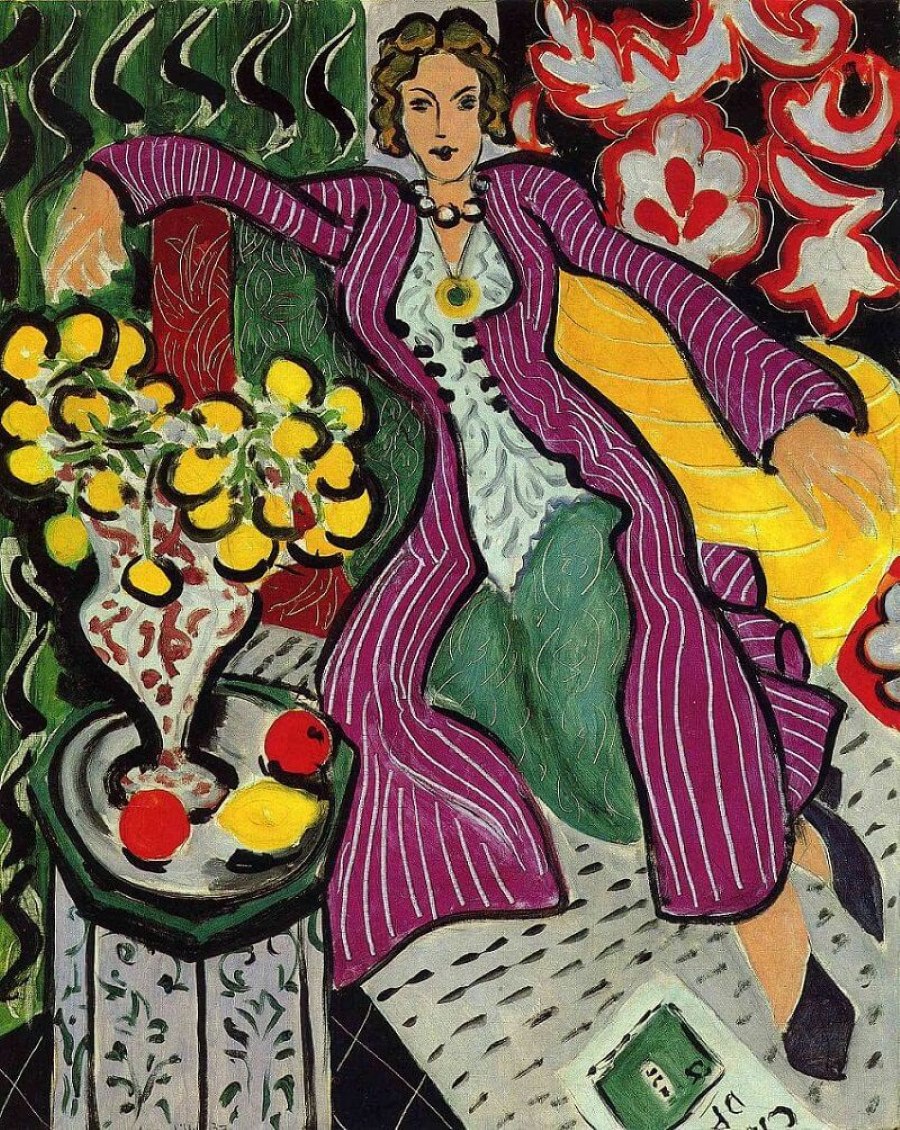

Woman in a Purple Coat, Henri Matisse, c. 1937 © Wikimedia Commons

Woman in a Purple Coat, Henri Matisse, c. 1937 © Wikimedia CommonsAn orphan and a refugee from the Russian Revolution, Lydia Delectorskaya started as Henri Matisse’s 22-year-old studio assistant and ended up his primary caregiver and trusted creative partner, by his side for over 20 years until his death in 1954. She ran his studio, organised the models, dealt with the dealers, sales people and the gallery. So involved was she in Henri’s life that Amelie, his wife of 40 years, gave him an ultimatum — "me or her". He chose his wife, before she left anyway and he asked Lydia to return.

But ‘Madame Lydia’ was much more than Matisse’s lover. As his biographer Hilary Spurling notes, he was too committed to his work to waste time and energy having sex with models:

If Matisse made love to Lydia, it was on canvas.

In fact, it took three years before Matisse asked Lydia to sit for him and he maintained an avuncular affection for his ‘ice princess’ until death, gifting her valuable paintings to set her up for the future.

Lydia posed for such paintings as The Pink Nude (1935), The Romanian Blouse (1940), Woman in a Purple Coat (1937), Blue Eyes (1934) and Le Rêve (1935) and devoted the rest of her life to working with the artist’s heritage.

She committed suicide at the age of 84, and her last desire was spelled out in a note that read:

Please put Henri Matisse’s shirt next to me.

4. Gala Diakonova

Galaria, Salvador Dalí с. 1940-1945 © Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres

Galaria, Salvador Dalí с. 1940-1945 © Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, FigueresDespised by the likes of André Breton and Luis Buñuel, Salvador Dalí’s life partner Gala Diakonova is nevertheless a formidable female face of the Surrealist period. Described as avaricious, sexually voracious and even demonic, it’s documented that she’d stub cigarettes out on people’s arms and spit in their faces if she didn’t like them.

Perhaps then a fitting muse for the Surrealist provocateur, Diakonova was not just a source of inspiration but a powerhouse of art business, instrumental in identifying Dalí’s potential as a bashful 24-year-old and propelling him to international stardom as El Maestro. Gala acted as Dalí’s agent, dealer, promoter and publicist, channelling her ruthless energy into his promotion and protection for fifty-three years. Her role as a guiding force was so critical that from 1950 onwards, Dalí signed many of his paintings Gala-Dalí in honour of her contribution to both his artistic process and status as an icon of modern art.

Following Gala’s death in 1982, Dalí holed himself in Púbol castle, refusing to eat and never painting with the same bold vibrancy and artistic courage again. In his own words, it was mostly with her blood that he could paint his pictures, and that had run out.

5. Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera

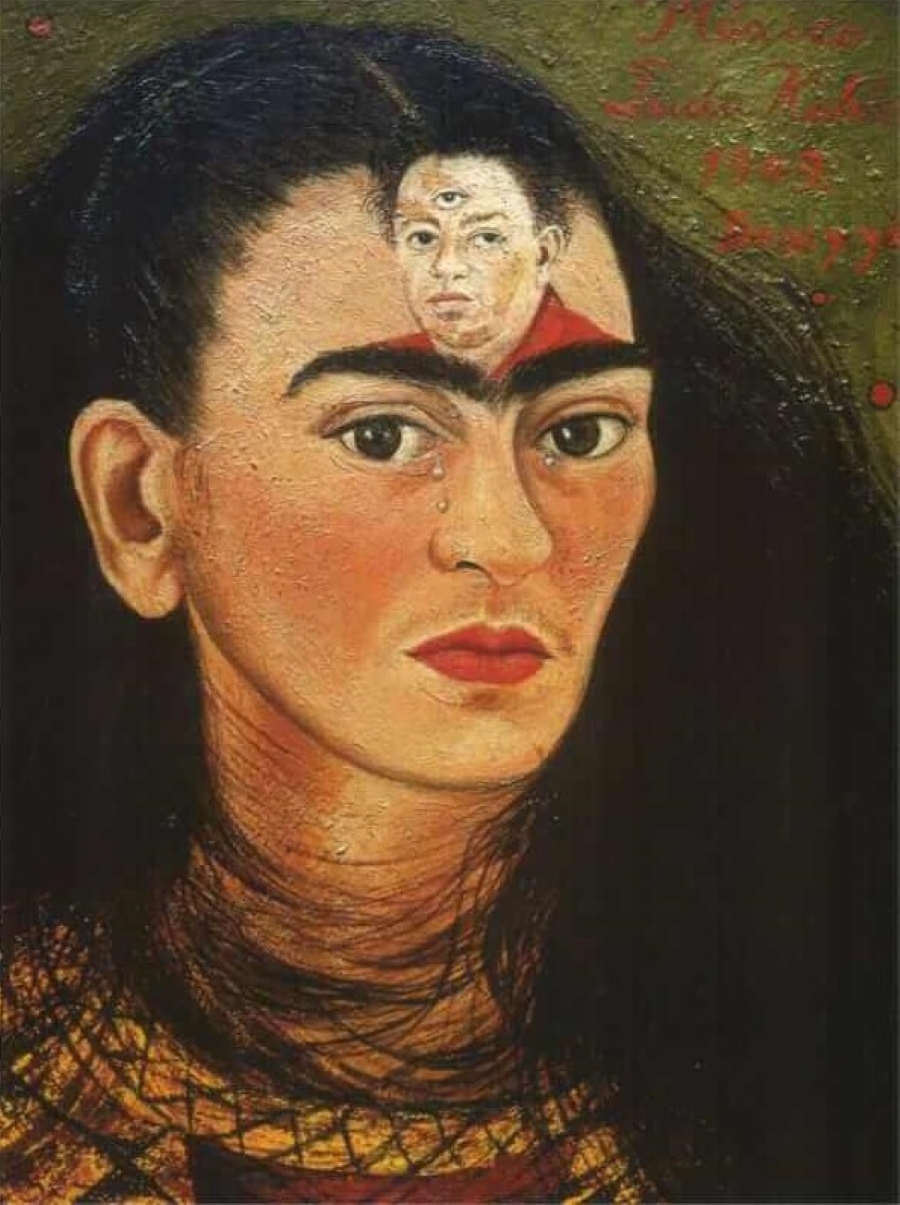

Diego y yo, Frida Kahlo, с. 1949 © Wikipedia Commons

Diego y yo, Frida Kahlo, с. 1949 © Wikipedia CommonsAlthough Frida and Diego oscillated between artist and muse during their passionate affair, Kahlo’s creative fascination with Rivera was more introspective than idealising, painting a picture of love as a muse for self-concept and self-actualisation.

Originating as more conventional portraits of the couple and transforming into self-portraits with Rivera emblazoned on her chest and the centre of her forehead, this shifting interpretation of the couple’s relationship alludes to Kahlo’s perception of Rivera as the very lens through which she perceives her reality, in both heart and mind.

Diego and I (1949) is at once a vulnerable expression of anguish in response to Rivera’s affair with María Félix and a striking portrait of love’s power to redefine the self. We imagine Kahlo gazing at herself to paint this portrait, and meeting Rivera’s third eye in her reflection.

Despite the reality of his wandering eyes as demonstrated in the portrait, her connection to him on a more spiritual level during this vulnerable moment signals a deep and unspoken bond that has permeated her very self-perception. He no longer sits outside of her sense of self, but as part of it.

As an Art de Vivre subscriber, make sure you also delve into the history of the Venice Biennale.

Credits for the Main photo: Ophelia, John Everett Millais, c. 1851–1852 © Tate Britain, London via Wikipedia Commons