Q&A with anti-war artist Anna Dial: “Making art in Russia is like a game of roulette.”

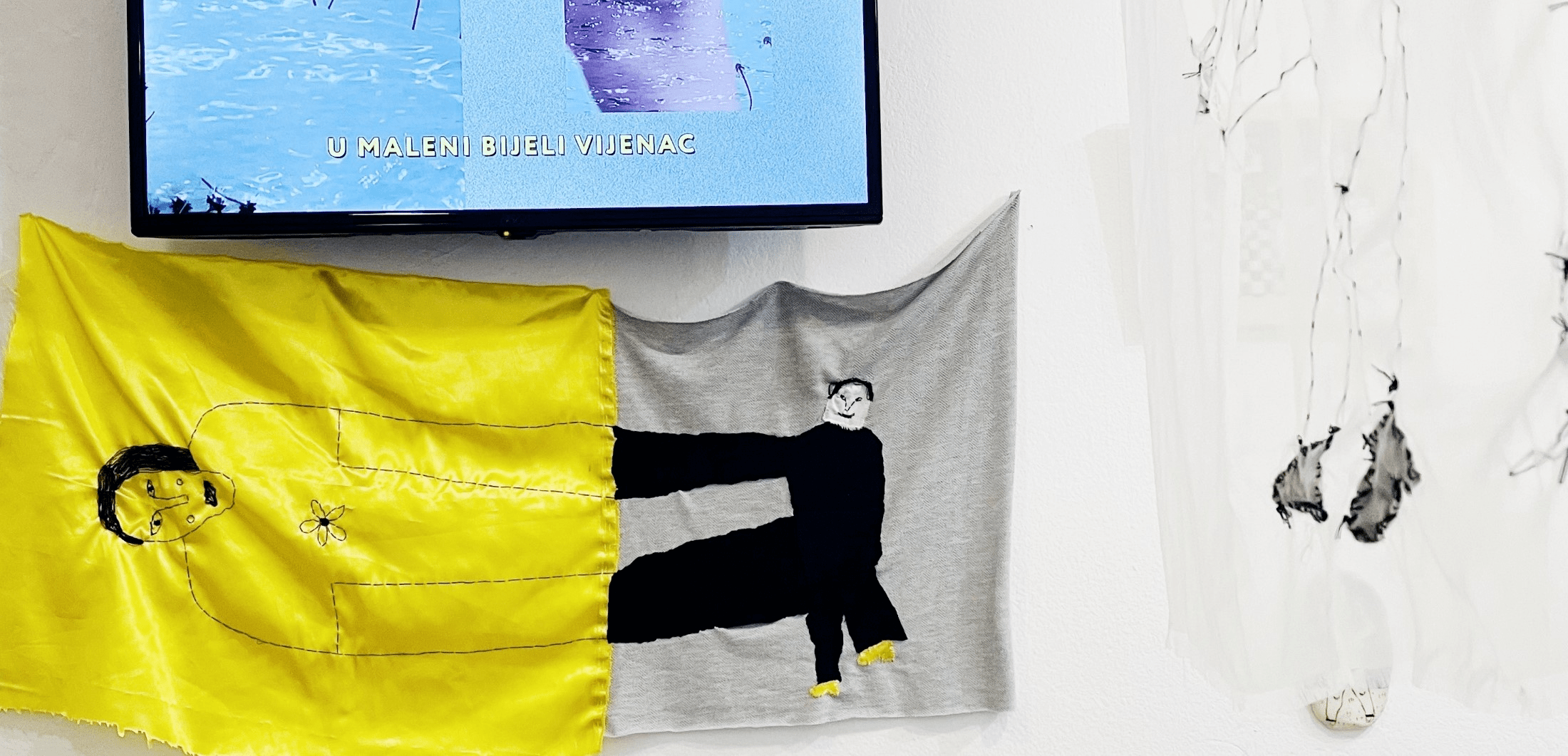

Russian multidisciplinary queer artist Anna Dial, co-founder of the platform ‘Unknown Person’ and the educational project Kafedra, moved to a small coastal town in Montenegro towards the end of 2022 with one main goal: to open a gallery with the mission to support anti-war art.

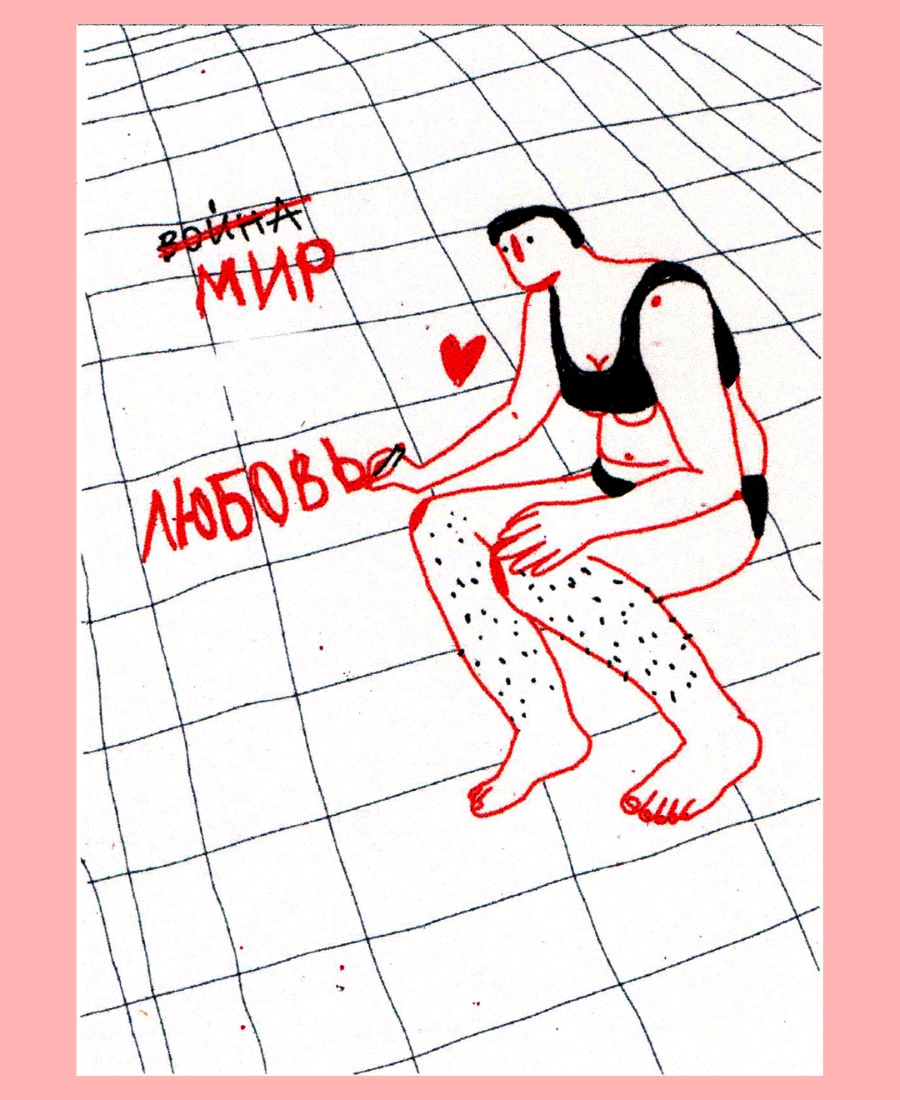

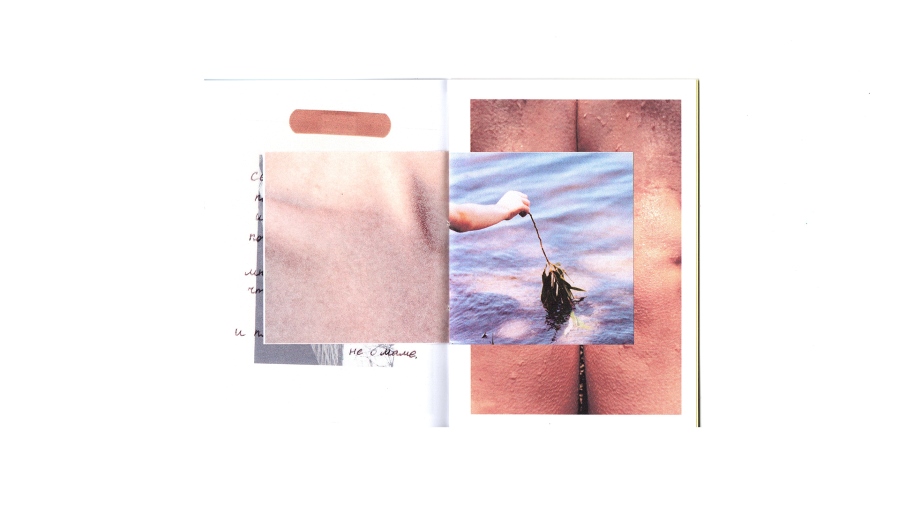

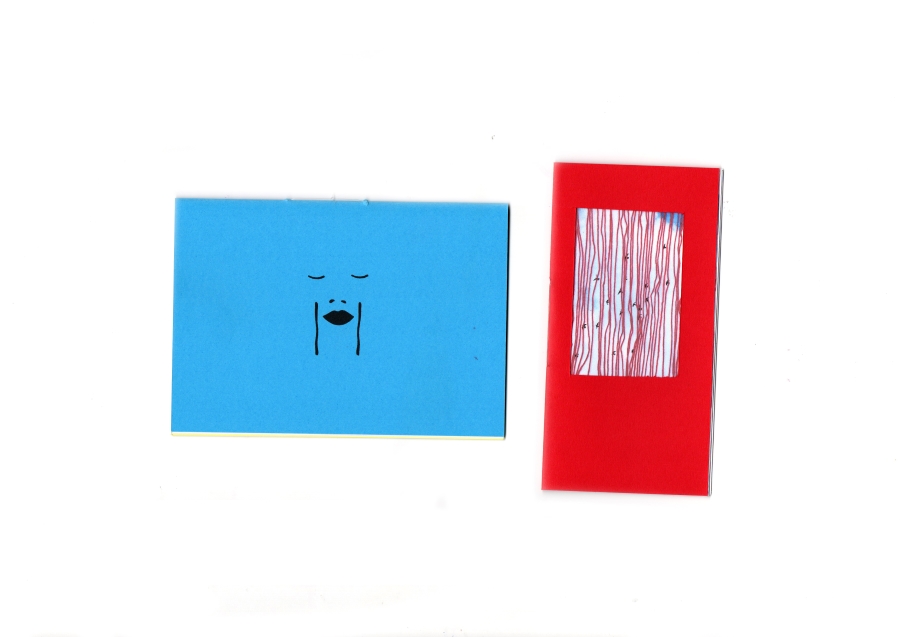

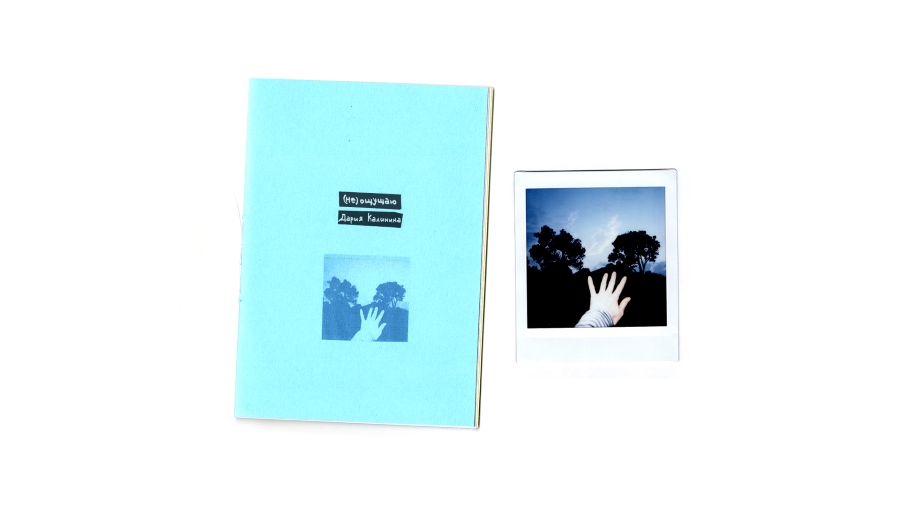

Dial, who is also an art teacher and has published over 50 small print editions, addresses the ideas of feminism, democracy and post-utopia in her work, and works hard to create visibility around the issues affecting queer people and climate refugees.

She works with animation, illustration, sculpture, painting, and embroidery and regularly takes part in contemporary art festivals and exhibitions. Her graphics, paintings, printed editions, and art objects are held in private collections, galleries and museum archives such as the The Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow.

Born in Kamchatka, in the Russian Far East, Dial moved to Moscow after graduating from university. Since the end of 2022 she has moved to Montenegro.

Here she tells us why she moved to Montenegro after the war started, how she came to open her own gallery, and the challenges of creating anti-war art in Russia.

What is your art about? What are the main themes you delve into in your works?

I identify as a queer artist and feminist. Often my characters are not gender specific, I play with shape and body image and give the viewer the freedom to feel the story. I have a series of feminist works and comics, and I have a project called ‘46 degrees Celsius’ in which I explore problems related to global warming. Sometimes I turn to very personal issues.

Moving to another country is a brave step. Why did you decide to do it?

A number of laws have been adopted in Russia, which no longer allow free artistic activity. And if you create samizdat [a form of underground publishing and distribution of written materials that were critical of the Soviet government and its policies], that’s a red flag for the state.

During 2022, there were a few moments that prompted me to leave: On several occasions certain people made photographic recordings of my anti-war and printed samizdat materials. Unfortunately I can't reveal everything publicly in detail. I was in my last term of pregnancy at the time, when all this was happening. I didn't feel safe. My family and I left urgently at the end of the year, and all this against the backdrop of military mobilisation that had already begun. Making art in Russia in spite of it feels like a game of roulette: it doesn't matter whether you are famous or not — they will find something to punish you for.

Some of your colleagues were forced to leave Russia and others were imprisoned for their anti-war stance (Sasha Skochilenko has been in jail for more than a year for "anti-war price tags" in a store; Lyudmila Razumova and Alexander Martynov were imprisoned for anti-war graffiti; Philippe Kozlov (Philippenzo) was recently arrested for his anti-war graffiti. Do you think it is possible to make art in Russia today if you raise anti-war themes?

Some artists continue to create anti-war art that supports those who still remain in Russia and are against the war. When I come across posts with such art projects, of course I started to worry about my colleagues. Nowadays, any art that even indirectly hints at an anti-war stance can be criminalised.

In the spring of 2022, I took part in a contemporary art fair in Winzavod, Moscow, and two girls came up to my stand and said:

Don't buy this work, it looks like the Ukrainian flag, take the rainbow man, rainbows have not been banned yet.

And that was only because my ceramics had blue and yellow colours.

My small publishing house was flooded with letters saying

please remove my work due to new laws

or refusing to have their name in our collective project.

Before leaving Russia, I had to remove a lot of material from my media. It is very difficult and dangerous to create in such an environment, especially when you have children. I was disgusted with myself because of self-censorship, because of fear every time. It took a very long time to come round again.

Those who are now in prison for freedom of speech, art, for their anti-war stance are the heroes of our time.