The art of attribution: The remarkable journeys of 3 masterpieces

The world of art is an enigma. Who created the masterpiece? When did the artist bring it to life? What story does it tell, and who are the mysterious figures within? These questions are the main keys to understanding any art work. Yet, it is in the midst of this complexity that some of the most intriguing stories come to life.

When looking at old masterpieces, museum experts struggle to decipher the myriad mysteries surrounding the attribution of these artworks. They diligently set out to determine the creation date, unravelling the narrative, identifying the depicted characters and locales, and, above all, ascertaining the true authorship. While some attributions may prove straightforward, others reveal narratives so convoluted that the process of discovery unfolds over years, offering a real challenge.

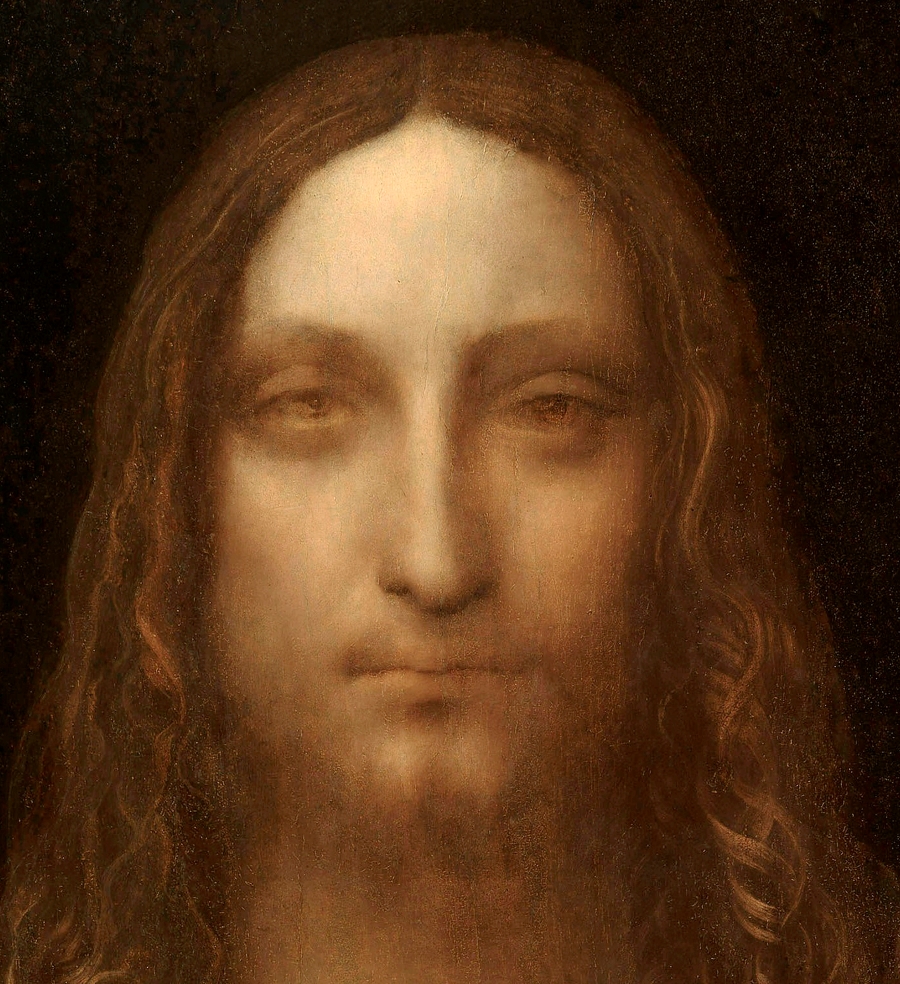

'Salvator Mundi' by Leonardo da Vinci: The masterpiece's journey

Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci

Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da VinciIn 2005, two New York art dealers, Robert Simon and Alex Parish, attended a small auction where they purchased a quite small oil painting in poor shape. ‘Salvator Mundi’ (c. 1490-1500) depicts Christ with long wavy hair, looking at the viewer. His right hand is raised in a gesture of blessing, and in his left hand, he holds a crystal ball, which symbolises him as the saviour of the world.

Acquiring the painting was just the beginning of an extraordinary journey. 'Salvator Mundi' had suffered from shoddy prior restoration attempts, making it nearly impossible to discern the hand of the renowned Renaissance master, Leonardo da Vinci. Moreover, the wooden panel supporting the artwork was infested with worms, continually threatening its integrity. Despite these challenges, Simon and Parish decided to take a gamble on the painting's potential and buy it.

Recognising that this painting needed some renovations, they took it to art conservator Dianne Modestini, specialising in old master and nineteenth-century paintings. Modestini oversaw the painstaking reconstruction of the wooden panel and meticulously removed layers of excess paint. As she worked, a revelation emerged: 'Salvator Mundi' could very well be a lost masterpiece by Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519).

Salvator Mundi (details) by Leonardo da Vinci

The painting as a lost masterpiece by da Vinci was first shown in 2011 at the London National Gallery at an exhibition of the artist. At this time British auction house Christie’s hailed it as the artistic rediscovery of the 21st century. Later in 2017 this painting was sold at Christie’s New York for a record-breaking $450 million and disappeared for a long time without any trace. So now the whereabouts of ‘Salvator Mundi’ remains unknown.

Nevertheless, the questions over the authenticity of ‘Salvator Mundi’ have loomed since its first attribution. It was examined by curators and scholars multiple times. The use of characteristic for da Vinci’s sfumato, the reflections in the orb in Christ’s hand, the styling of the drapery, the curly hair and other details were marked as characteristic for the Renaissance style of da Vinci. However, the extensive restoration made it difficult to assess the quality of the original.

Some scholars think that this painting could have been updated by Leonardo or his apprentices. Artists who employed journeymen and kept apprentices often allowed them to imitate the master's technique to paint "unimportant" elements, such as hands. This was done either to improve performance or as exercise. Some of the studies claim that Leonardo depicted only the head and shoulders of Christ, and the arms and hands may have been added later. Nonetheless, conflicting viewpoints persist among experts.

The fascinating attribution puzzle of 'Salvator Mundi' has sparked the creation of a documentary by Antoine Vitkine, delving into the captivating investigation behind this enigmatic masterpiece's journey.

Johannes Vermeer and Hans Van Meegeren

The Supper at Emmaus by Han van Meegeren

The Supper at Emmaus by Han van MeegerenDutch painter Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) left behind only around 60 works. In the 19th century, Vermeer's art received little scholarly attention, but the scarcity of his pieces made them highly coveted by collectors. This rarity created an opportunity for unscrupulous individuals to dabble in art forgery, and one of the most cunning of these forgers in the 20th century was Dutch painter Hans van Meegeren (1889-1947), who targeted Vermeer as his unwitting victim.

In 1945, Van Meegeren found himself arrested for his collaboration with the German government during the occupation of the Netherlands. His newfound wealth during this period, along with his sale of an alleged early Vermeer painting titled 'Christ with the Adulteress' (1942) to Hermann Göring raised suspicions. However, during the investigation, Van Meegeren not only vehemently denied the accusations but also astounded everyone with an unexpected defence—he claimed that the painting in question was not a Vermeer at all; he had painted it himself. In his eyes, being accused of forging a work of art was preferable to the grave punishment he faced for wartime activities.

In reality, Van Meegeren had crafted numerous forgeries, not just of Vermeer's masterpieces but also works by other Dutch painters of the 17th century. These skillfully executed fakes were successfully sold as long-lost and recently rediscovered treasures. Many art critics and museums fell under the spell of Van Meegeren's imitations, exhibiting these paintings as genuine Vermeer masterpieces.

Woman Playing the Cittern by Han van Meegeren

Woman Playing the Cittern by Han van MeegerenTo create convincing forgeries of 17th-century masterpieces in the 20th century, Van Meegeren employed various tactics. He purchased old paintings, meticulously removed the top layers of paint, and then painted on the original canvas to give them an appearance of age. He even used 17th-century paints, primarily composed of natural pigments. These cunning methods enabled him to dupe art experts and scientists, long before the advent of modern technological tools for in-depth art analysis.

To escape a harsh punishment, Van Meegeren needed to prove his forgery skills. While under house arrest, he undertook the challenge of crafting one more painting, closely imitating the style of old Dutch masters. This endeavour successfully convinced everyone of his artistry in forgery. Consequently, Van Meegeren received a relatively lenient sentence of one year in prison for forgery. However, he never served that sentence, passing away in prison from natural causes less than two months after his trial, leaving behind a legacy as one of the most audacious art forgers in history.

‘Judith beheading Holofernes’ by Caravaggio

Judith Beheading Holofernes by Caravaggio

Judith Beheading Holofernes by CaravaggioIn 2014, a remarkable discovery emerged from the depths of an attic in a sprawling house in Toulouse—an artwork portraying 'Judith beheading Holofernes' that bore an uncanny resemblance to the masterful works of Italian artist Caravaggio.

For two years, the world remained unaware of this find until it was unveiled to the French Ministry of Culture in 2016. The government promptly imposed a 30-month export ban on the painting, allowing the Louvre to deliberate whether to acquire it. The museum declined the offer, and in 2018, authorities permitted the painting's sale on the open market.

However, doubts concerning the painting's authenticity remain. According to accounts from Caravaggio's contemporaries, he appears to have created two versions of this iconic composition. The first resides in Rome's Palazzo Barberini, while the whereabouts of the second, crafted in Naples, has long remained a mystery. References to this mythical second version appear in a 1607 letter by Flemish painter Frans Pourbus the Younger (1569-1622), who claimed to have seen the painting alongside the painter and art dealer Louis Finson (1580-1617), a follower of Caravaggio. Nonetheless, gaps in the painting's history persist, a void partly attributed to Caravaggio's fall from favour in the art world from 1650 to 1950 when his works held little value and remained overlooked.

There is evidence that Finson created a copy of ‘Judith beheading Holofernes’, leading art critic Mina Gregory to assert that the newly unearthed painting likely belongs to him. Those in support of Caravaggio's authorship point to the overall quality of the artwork and the presence of pentimento, the artist's corrections made during the composition's creation—a characteristic seldom seen in mere copies.

In 2019, the painting was slated for auction at Labarbe, with a preliminary valuation ranging from 100 to 150 million euros. However, it found a buyer prior to the auction—the new owner of ‘Judith and Holofernes’ is none other than American billionaire and philanthropist James Tomilson Hill.

Attribution in the art world often unfolds as a captivating detective story, filled with unexpected twists—a tale of art crime or an astonishing revelation. Yet, it remains a meticulous and vital undertaking led by attribution specialists, art restorers, and museum professionals who unveil the stories behind these canvases, shedding light on their rich histories and secrets.

For more insights into the history of art, check out our sneak peak of the Borghese art gallery in Rome.

Photo Credits: © Wikimedia Commons